Waiting at a stoplight, there’s sometimes a brief instant when all the turn signals of the cars in front of you sync together. Maybe you were zoning out, watching your windshield wipers, listening to the soft murmur of the radio, but in that moment, you snap to attention. What might be even more satisfying is when they begin to pull apart from each other again, creating an increasingly complex sequence. It feels magical: Each signal drifts into its own zone before gradually locking back together for another few beats of synchronicity.

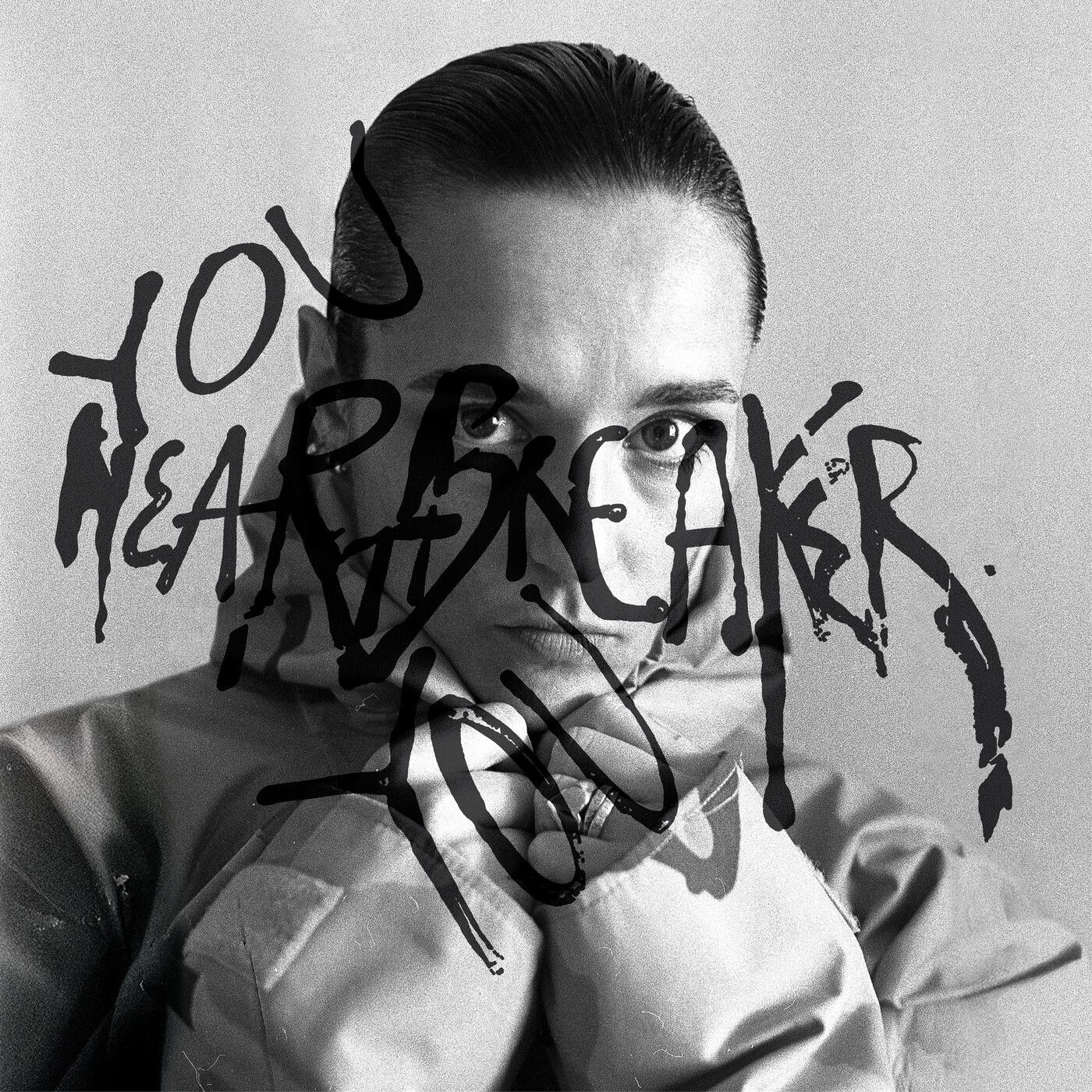

The members of Flur, the London-based jazz trio of harpist Miriam Adefris, saxophonist Isaac Robertson, and percussionist Dillon Harrison, understand this dance. Throughout Plunge, their spellbinding debut, there are stretches of time where each player operates at their own speed, pulling notes from their instruments as instinct dictates. They flicker around one another, drawing closer until they fuse in harmolodic structure, only to peel off into their own respective orbits. Let the record play in the background, and its shimmering atmosphere humidifies the room. Tune in to its dynamism, and you’ll discover a universe unto itself, a mesh of angular cadences, weightless tones, and denticulate textures.

The sounds mimic Flur’s origin story: The three met while studying music at Goldsmiths, University of London, and although they were all taking different courses, they became acquainted while playing in the myriad ensembles populating the vibrant scene adjacent to the college. Their individual resumes are stacked: Harrison plays drums for art punks Morgan Noise and Argentine kitchen-sink psych artist Gal Go; Robertson is a member of experimental punk outfit Parade and half of electroacoustic duo Wetroom with pianist Jack Elliott Barton; Adefris has played with Floating Points, Shabaka Hutchings, and vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Ganavya. Eventually, they coalesced into a trio. Led by Adefris’ harp, Flur fuse composition and improvisation, landing on a vaporous style somewhere between Alice Coltrane’s astral incantations and Uhlmann Johnson Wilkes’s interlocking kosmische.

Plunge plays like a long dissolve, the spindly rhythms of its front half slowly losing their rigidity, the way smoke tendrils dissipate as they rise. In the first five songs, each performer takes a turn directing the pulse, allowing the other two to stretch out and roam around the meter without fully straying from it. Suddenly, they’ll fit like zipper teeth, as in the middle of “Larking,” where Harrison drops percussive hits into the spaces between Adefris and Robertson’s dueling patterns. On “Bolete,” Harrison and Adefris erupt in parallel flurries of circular 16th notes, somersaulting over Robertson’s sustained drones. Occasionally, the scaffolding breaks apart: Opener “Nightdiver” swells to a billowing middle section that threatens to evaporate altogether, and “The Improve” begins and ends with copious amounts of space between each sax warble and struck string. These passages serve as foreshadowing for Plunge’s second half, where, instead of jumping back into more tightly composed melodies, the trio absorbs into each other like droplets of mercury.

The group’s metabolism slows significantly with “5 Sep,” which lumbers along with an almost doom-metal groove, patiently building into a massive wall of spacey synthesizers and Robertson and Adefris’ twin soloing. As the song ends with a gorgeous glissando from Adefris, all elements except for a shaker melt away, pooling together in the climactic diptych of “Trimaran i.” and “Trimaran ii.” It’s here that Flur demonstrate their full power—though they’ve spent so much time showcasing their formidable chops, “Trimaran” displays their restraint. Adefris’ delicate strums form an undulating bed, and both Robertson and Harrison seem to dare each other to play, issuing notes like a child hesitantly jumping into double-dutch ropes. These are the least busy but most powerful moments on Plunge, a remarkable understanding of how quietude can be urgent—how silence can be more commanding than volume.

“Hold Fast Old Kelp” divides the album’s discrete sections, and it’s the strangest, most enthralling cut on the album. It starts like an outtake from Boards of Canada’s The Campfire Headphase, Adefris’ harp sanded down by a murky low-pass filter, then buried beneath a cello-like hum. The track doesn’t resemble anything that comes before or after, more Daedelus than Dorothy Ashby, but also doesn’t feel out of place. It’s the only time on the record when all elements dress the lines, snapping to an almost quantized grid. But it’s only two minutes long, the length of a light cycle. From here, everything follows its own internal beat, never to converge in the same configuration again. Flur revel in these instances of chance connection, adept at setting them up, but more interested in their serendipitous arrival. Each one is singular and special, worthy of the space and attention we give them.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.